Analysis

Exclusive: Toronto currency shop in RCMP leak case tied to $3.5-Billion in Fintrac reports

In late 2014 Salim Henareh — a Toronto currency shop owner targeted by the Five Eyes as the financial intermediary between Canada’s Big Five banks, Hezbollah’s Dubai-based terror financing kingpin Altaf Khanani, and Middle Eastern organized crime cells in Canadian cities — was identified by Canada’s money laundering watchdog in an astounding $3.5-Billion worth of transactions, according to a sensitive report leaked by Cameron Ortis, the Mountie’s former intelligence director.

And in March 2015, when Ortis illegally shared hundreds of related Fintrac reports to Salim Henareh and warned him of a nascent RCMP investigation, it caused an international “ripple effect” that not only helped Henareh and Khanani’s global money laundering network, but could have enabled their clients to evade financial regulators, a jury in Ottawa heard this week.

Retired RCMP staff sergeant Patrick Martin, a Toronto financial crimes investigator on Project Oryx, which targeted Salim Henareh and Khanani’s Canadian agents, testified he had no idea Ortis had leaked Martin’s investigation plans and related Fintrac documents.

“This was very early on into Project Oryx, the first month, so the fact that Mr. Henareh was being advised he was being looked at by RCMP,” Martin said, “has an effect on everything.”

Two weeks into Ortis’ long-awaited trial the jury’s considerations have become clear.

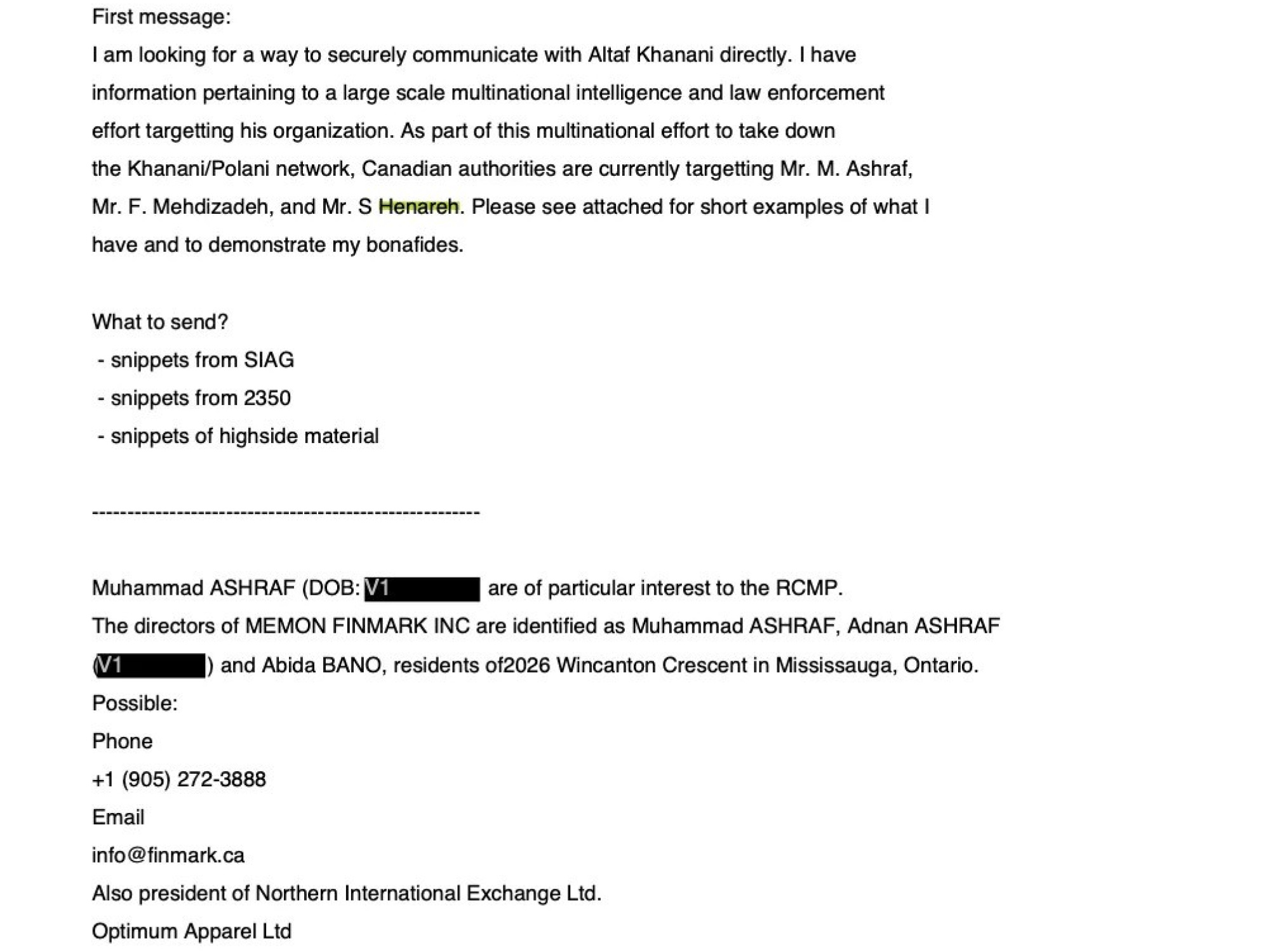

Ortis is accused of seeking to profit by helping Khanani’s network evade Five Eyes investigations. He’s also accused of seeking to profit from high-tech criminals in Vancouver that offered uncrackable Blackberry phones to clients including Khanani and Mexican cartel bosses.

In doing this, Ortis risked the lives of undercover police officers and agents, two RCMP officers have testified. Ortis, on the other hand, claims he had authorization to share RCMP secrets.

In cross-examinations of RCMP witnesses, Ortis’ lawyers are implying Ortis had “carte blanche” while running undercover operations against Khanani’s network from within Operations Research, the secretive RCMP intelligence unit Ortis headed. This unit had access to top secret signals intelligence from Canada’s more powerful allies.

The United States and United Kingdom are watching the trial very closely, and foreign law enforcement agencies could be interested in prosecuting Ortis, according to an intelligence source not authorized to comment publicly.

But aside from questions of whether Ortis will go to jail in Canada and what damage he may have done to the Five Eyes, The Bureau’s analysis of 500-pages of sensitive documents filed by prosecutors in this trial raises new questions about the integrity of Canada’s banking industry and the government’s inability to regulate money laundering.

FBI and RCMP intelligence target Henareh

In late 2014, when the RCMP mounted a high-priority investigation in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, in partnership with the United States and Australia, Khanani, an international financial operative for the Iranian state-sponsored military and crime group Hezbollah, was Target One.

The Canadian side of the probe, Project Oryx, initially focused in two areas. One was a group of politically-connected Iranian-community leaders in Toronto that ran currency shops and immigration-investment businesses.

The most prominent currency trader, Salim Henareh, often appeared with Canadian politicians and reportedly attended a $5,000-per plate “cash-for-access” fundraiser for Ontario Liberal Party premier Kathleen Wynne, in 2014.

At that time, Henareh and his business, known as Rosco Trading and also Persepolis International, had been on the radar of Fintrac and the RCMP for about ten years, Ortis case records show. But money laundering investigators found him hard to pin down.

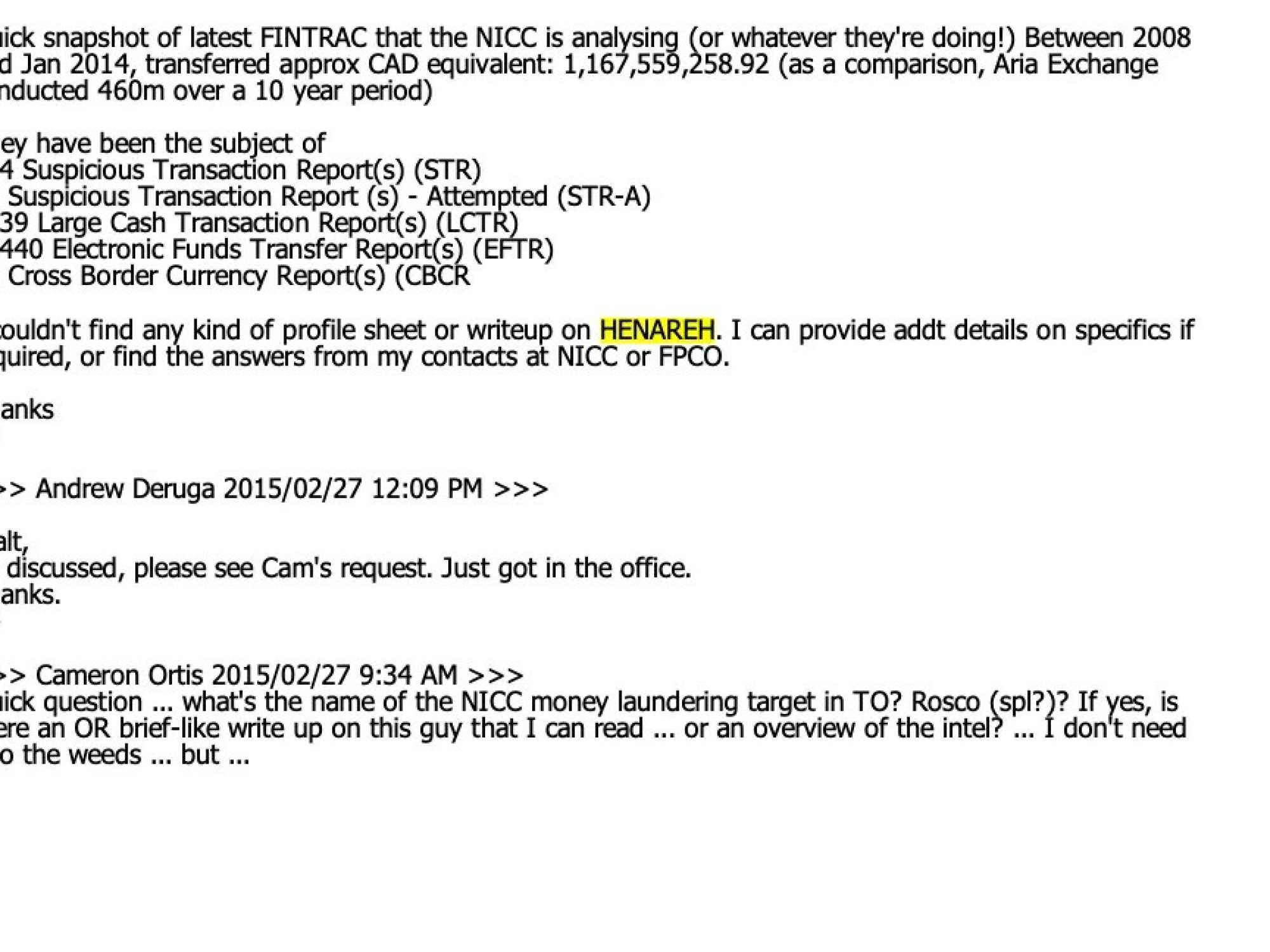

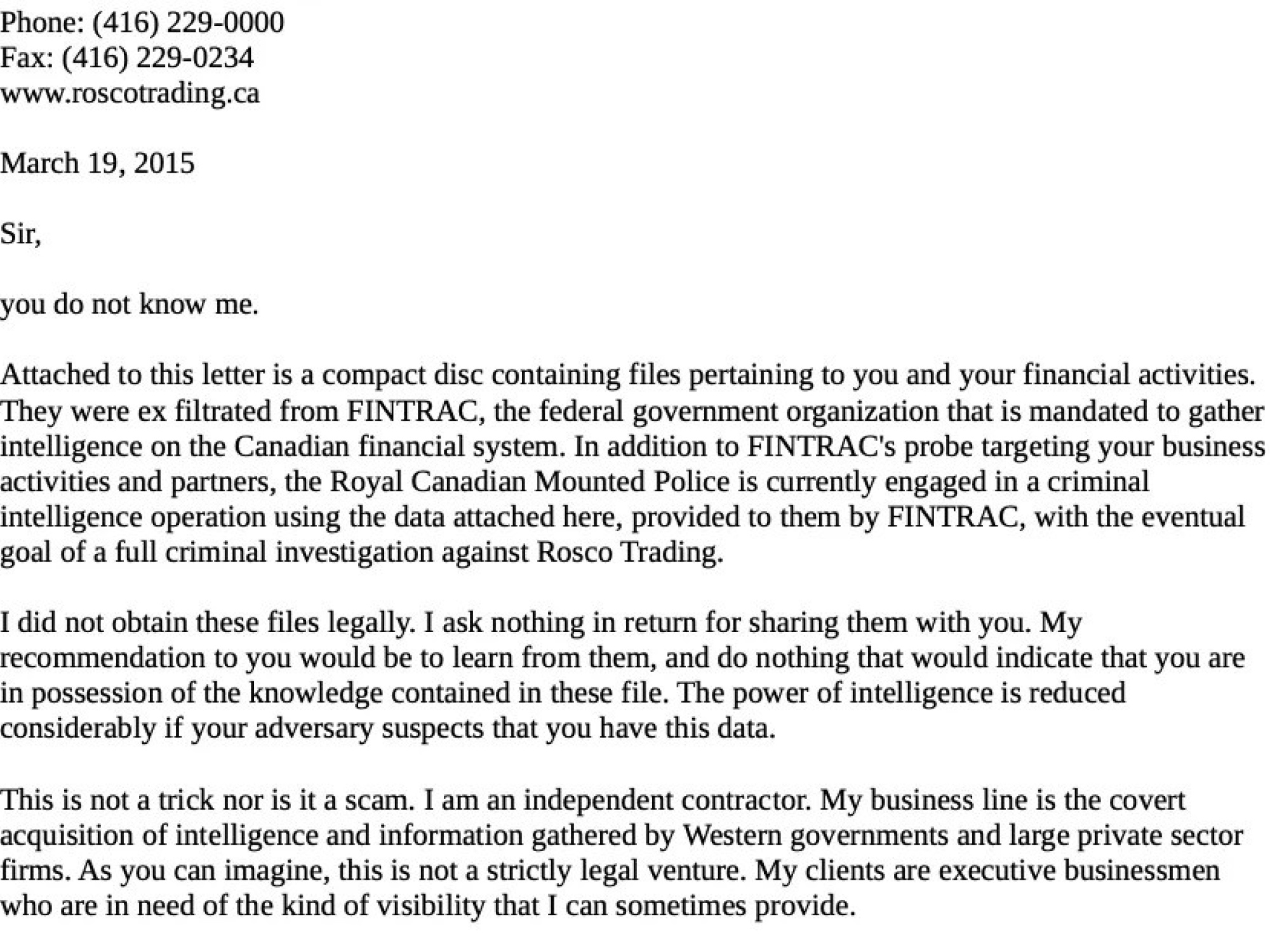

A few weeks before he approached Henareh in March 2015 with an unsolicited, “no strings” proposal — a voluminous Fintrac leak in exchange for future business considerations — Ortis gathered intel on Henareh from his Operations Research analysts.

“HENAREH was unsuccessfully targeted by RCMP in 2007. In that case UC's [under cover officers] went on several occasions to drop off money to Rosco and his people,” an email from an RCMP subordinate to Ortis said.

“A UC mentioned something to one of Salim's guys about the money being dirty.

The worker just walked away without picking up the money.

Despite their being resounding amounts of circumstantial evidence, Crown refused to lay charges because they didn't have anything concrete that could prove they were knowingly moving dirty money.”

The second focus of Project Oryx was smaller currency shops in Mississauga and Toronto that had links to Pakistan, and also did business with Henareh and Khanani.

These shops would be surveilled, a January 2015 Project Oryx case plan written by Staff Sgt. Martin said: “with the objective to lead investigators to other associated Greater Toronto Area Money Service Businesses and their nexus to drugs, organized crime and/or terrorist financing.”

Oryx’s goal was disrupting money laundering in Canada.

But the broader international goal of the Five Eyes partners — guided by elite U.S. counter-narcotics officials that explained their objectives toThe Bureau — was disrupting Hezbollah’s shocking capacity, via Altaf Khanani and other major Hezbollah money launderers in Canada, to turn drug money into funding for weapons and soldiers used by Iran and its proxies in Middle Eastern wars and terror attacks.

“The whole point was, you can’t have conflict zones explode overnight, without the people that fund the terrorists and move the drug money,” a former U.S. official involved in the Khanani probe informed The Bureau, prior to the start of Ortis’ trial in Ottawa.

A previously unexamined concern in Khanani’s case, though, has been how drug cash collected in Canadian cities finds its way from strip mall currency shops into Canada’s Big Five banks, before getting wired to the Middle East.

For the first time, sensitive records seized from Ortis and filed by Canada as evidence in his prosecution, reveal the role Salim Henareh is suspected to play.

Rosco Trading appears to be an intermediary

Despite the new evidence in Ortis’ trial, and also a 2021 United States criminal complaint that accuses Henareh’s Canadian businesses, Persepolis International and Rosco Trading, in a massive Iran sanctions evasion scheme, Henareh has repeatedly denied any wrongdoing.

On Thursday, the jury heard that Project Oryx grew out of a September 2014 intelligence report from RCMP’s National Intelligence Coordination Centre (NICC), which was based on Five Eyes intelligence.

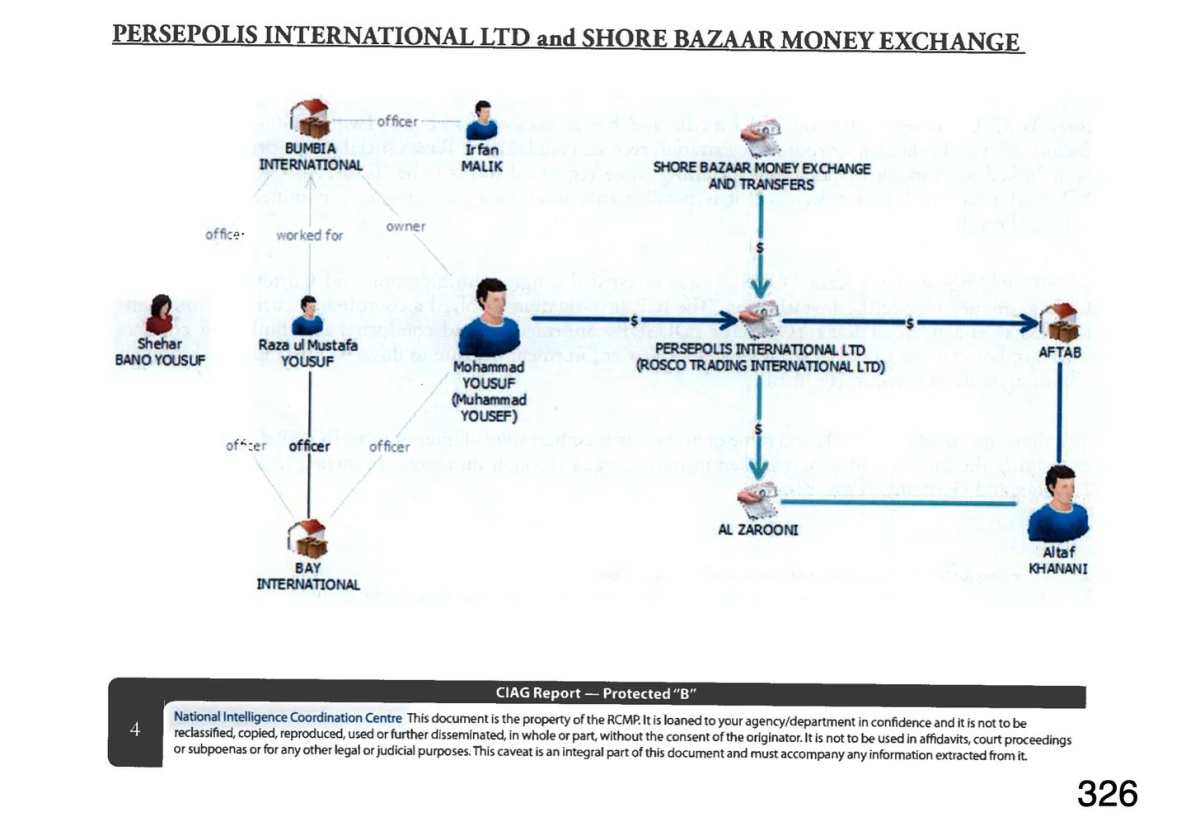

At that time, records seized from Ortis show, NICC and the FBI were looking into Persepolis International and Rosco Trading.

The September 2014 NICC report says that Persepolis International, “is known to law enforcement for its involvement in international money laundering and, in particular, the movement of money to and from Iran.”

It adds that NICC’s analysis of RCMP and Canada Border Services Agency investigations “highlighted the use of Canadian-based PERSEPOLIS INTERNATIONAL LTD to conduct financial transactions by Canadian Middle Eastern organized crime.”

And, citing many hundreds of pages of financial records analyzed by NICC, the report said: “since 2002, FINTRAC has disclosed to the RCMP over $3.5 billion in financial transactions related to PERSEPOLIS.”

And yet, the report explained, these figures “should be considered understated as only a portion of actual financial activity between entities is reported.”

Thursday in court, Martin, the retired RCMP financial crimes investigator, said he used NICC’s September 2014 report to plan Project Oryx, but his team needed to turn NICC’s Five Eyes intelligence on Khanani’s network into hard evidence in Canada.

To do this they established surveillance on some of the smaller currency shops in Ontario that were collecting cash for Khanani’s companies Al Zarooni Exchange and Khanani and Kalia International, and somehow wiring it to Dubai, India and Pakistan.

Al Zarooni had been identified “as a priority threat by the Joint Narcotics Analysis Centre,” of the United Kingdom, due to “its use by organized crime and/or terrorist groups to launder the proceeds of crime,” Martin’s January 2015 Project Oryx report explained.

And, “the Australian Federal Police and the National Intelligence Coordination Centre have demonstrated analyses of Al Zarooni Exchange financial transactions originating from Canada and identified money transfers primarily to entities in the UAE, Pakistan and India,” the document concluded.

“That analysis demonstrates that Khanani uses the services of persons/businesses in Canada.”

The intricate detail of how this worked, Martin’s Project Oryx case plan said, was that Henareh basically functioned like an on-ramp to Canadian banks.

“Analysis of the data shows that Rosco Trading appears to be an intermediary for transactions with the Al Zarooni Exchange or Khanani and Kalia International in Pakistan for the other GTA-based businesses,” the report said.

Going into further detail, it explained how Fintrac analysts and NICC’s September 2014 intelligence report, found that Henareh’s currency shop received transfers from smaller Toronto area shops and in turn sent them offshore to Khanani in Dubai and Pakistan.

The reason for these complex intermediary transactions — according to Fintrac and the RCMP — was Henareh had solid business relationships with Canada’s international banks, which were used as a bridge to Khanani’s international accounts.

And the smaller shops “may not have the 'connections' or banking relationships with the large banks to accommodate these transfers.”

In other words, financial institutions need to be big enough, and have a good enough reputation, to send substantial funds from Canada into the world’s banking system.

Banks do not want to get flagged by Fintrac for dealing with shady financial operators. In theory, Canada’s Ministry of Finance could shut a bank down, if it was handling drug money or facilitating terror financing.

Martin’s January 2015 Project Oryx report explained the work around process like this.

“Money Services Businesses must have a good working relationship with the larger financial institutions because they need them in order to conduct the electronic funds transfers off shore. If the correspondent banking relationship with the MSB is questionable, the big banks will 'de-marketize' these MSB clients because they consider them high risk when doing this foreign exchange. This process is demonstrated in the FINTRAC disclosures when [another Toronto area currency shop] utilizes Rosco Trading to move money directly to Dubai.”

In court Thursday, the jury heard that Ortis leaked revealing portions of Martin’s detailed, seven-page Project Oryx report to Muhammad Ashraf, one of the smaller Toronto-area currency shop owners targeted by the RCMP along with Altaf Khanani and Henareh’s Rosco Trading.

“If subjects know that they're being watched by the RCMP, they may change their tactics, they may stop what they're doing altogether, and it would certainly affect our investigation," Martin told the jury. “It could jeopardize an ongoing investigation, in this case with the Australian Federal Police, and with the DEA in the United States.”

The jury has heard that Farzam Mehdizadeh, another Toronto currency shop owner targeted in Project Oryx in partnership with the DEA in Miami, somehow had the wherewithal to flee to Iran only days before the RCMP planned to arrest him in 2017.

“Mehdizadeh was moving money, cash, from the GTA and to Montreal,” Martin said. “Physically moving it himself.”

Ortis had emailed to Mehdizadeh’s son in early 2015, but was not proven to have reached Mehdizadeh with Five Eyes leaks on the Khanani probe, the jury heard.

Maybe not everything will be reported

Records from the National Intelligence Coordination Centre’s September 2014 intelligence report, and found on Ortis’ devices, have been redacted in court exhibits.

But what can be seen speaks to the sheer scale of suspected drug cash running through the currency shops targeted in Project Oryx.

One page of the September 2014 report that refers to smaller Toronto-area currency shops used by Khanani, says: “The above-noted [redacted] examining the import and export of heroin into Canada through numerous countries, including Australia, Pakistan and Germany.”

Another portion of that report says:

“[Redacted] has been investigated by the Toronto Police Service for money laundering. In 2009, the RCMP received a FINTRAC disclosure relating to suspicious financial transactions totalling $7,652,254.00 CAD, $86,991,571.94 USD and $299,187.00 GBP between November 2005 and September 2009.”

The report continues to name an Ontario numbered company linked to Khanani and Project Oryx targets in Toronto, and says “FINTRAC established that some of the money was going through gaming facilities in Ontario and Las Vegas.”

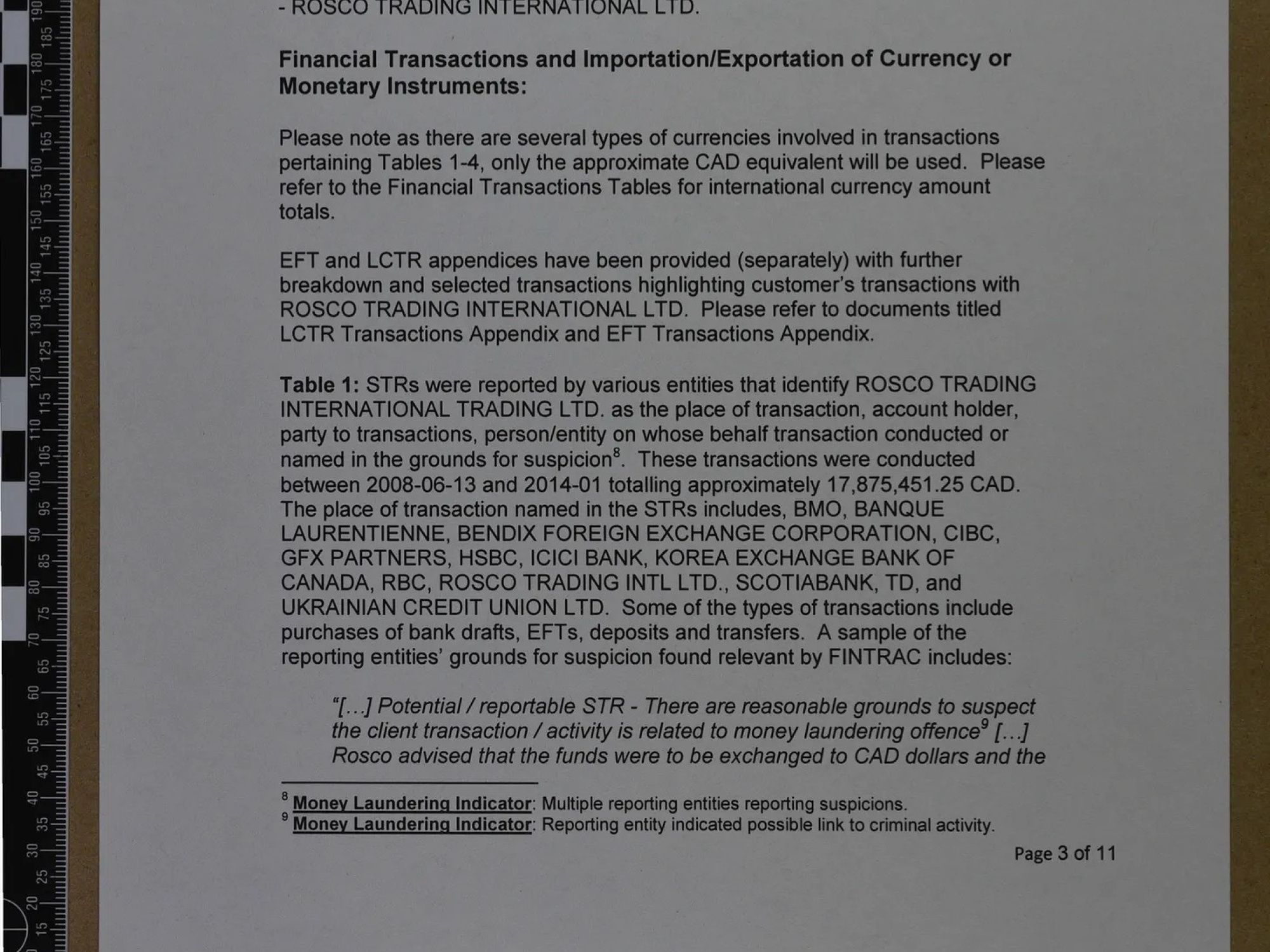

Crown prosecutors also questioned Martin on Thursday about an 11-page Fintrac disclosure report mailed to Henareh by Ortis, in March 2015.

The Fintrac disclosure reveals Henareh’s extensive list of Canadian and international banking partners, and points to numerous suspicious transaction reports, that were “submitted to FINTRAC involving transactions conducted at RBC, TD BANK, BMO, SCOTIABANK, CIBC, WESTERN UNION FINANCIAL SERVICES (CANADA) INC., BENDIX FOREIGN EXCHANGE CORPORATION, GFX PARTNERS INC., UKRAINIAN CREDIT UNION LIMITED, ROSCO TRADING INTERNATIONAL LTD., HSBC BANK CANADA, BANK OF AMERICA, SCOTIABANK, KOREA EXCHANGE BANK OF CANADA, ICICI BANK CANADA, BANQUE LAURENTIENNE DU CANADA and QUESTRADE INC.”

The 11-page record also provides a small sample of the reasons why Fintrac found some of these transactions problematic.

“Rosco advised that the funds were to be exchanged to CAD dollars and the funds originated in Dubai from customers to assist them with Immigration Investment needs,” one summary said. “Source of the funds from Rosco are unknown, but since Rosco has failed our compliance program and then attempted again to open a new account again in March 2010 makes us deem that the activity is suspicious.”

Another case involving immigration investment, said Rosco Trading “was previously a RBC client, which the relationship was terminated in 2009 for suspicious wires received from their account in Dubai and wires to another Money Service Business.”

On Thursday, Crown prosecutors asked Martin, the Project Oryx investigator, if he was aware “this 11-page Fintrac report and a CD containing all these tables including the Suspicious Transaction Reports were mailed to Mr. Salim Henareh?”

Martin said no.

The Crown followed up, asking what value the information could have to Henareh and others.

Martin said these Fintrac records showed that the U.S. Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Centre, RCMP, and OPP were examining Henareh and his financial counterparties.

Therefore, Henareh could potentially change his ways and tell his clients to as well.

“It would advise Mr. Henareh he was being looked at,” Martin said, “and that could have a ripple effect on any illegal activity they might be doing. Now maybe not everything will be reported [to Fintrac]. Or they will be more specific on what they report, on how they transfer their monies.”

Ministry of Finance alerted

Martin’s January 2015 Project Oryx report says that in December 2014, his “investigators met with members/analysts from Criminal Intelligence Service Canada, Criminal Intelligence Service Ontario, Ministry of Finance Analysts and OPP Intelligence Bureau to discuss current trends, criminal patterns and overlapping criminal patterns surrounding Rosco Trading and various crime groups in the GTA.”

The document says the Ministry of Finance was interested in Project Oryx’s primary targets and “they also have information available that is indirectly related to Rosco Trading.”

Canadian Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland and her staff did not respond to The Bureau’s questions regarding evidence in the Ortis case referring to the Canadian banking sector’s exposure to Rosco Trading.

This article originally appeared in The Bureau.