Commentary

Occupy Wall Street Redux

This article originally appeared in the Economic Prism.

“The bank is something more than men, I tell you. It’s the monster. Men made it, but they can’t control it.”

– John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

Negative Carry

Borrowing short and lending long works mostly well most of the time. This is how modern banking works. You may be a customer at a bank. But you also supply the product.

In short, a bank will pay you a small percent for the deposits in your checking and savings accounts, which you can withdraw at any time. This is the borrowing short side of the operation.

The bank then takes your deposits and invests the money in some longer-term assets, such as loans and bonds that aren’t paid back for years. Say the bank earns 2 percent on its money while paying depositors a fraction of a percent. The bank pockets the spread, the net interest margin. Easy money.

However, when the Federal Reserve intervenes in the market and presses the federal funds rate to zero and holds it there for 2 years (March 2020 to March 2022), driving yields across the range of maturities to 5,000-year lows, something bad is bound to happen.

The experience for consumers over the last 24 months has been raging consumer price inflation. But that’s only a small part of the bad stuff that can happen.

Because as the Fed jacked up the federal funds rate starting in March 2022, to contain the consumer price inflation of its own making, the yield curve has inverted. Short term yields are higher than long term yields. And banks, having borrowed short to lend long, have negative carry.

Perhaps it would all works out for the banks if depositors stayed put. But in a world where you can score nearly 5 percent from Treasury Direct – with no brokerage fees – why keep excess deposits in the bank when you only get a fraction of a percent?

It’s a good question…

Answering the Call

Customers at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) recently answered this question by pulling their deposits en masse. On March 9, SVB customers withdrew more than $1 million per second for 10 hours straight – totaling $42 billion – before the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) seized the bank and declared it insolvent.

This, in essence, was an old fashion bank run with a twist. The digital age pushed the bank run into hyperdrive.

SVB isn’t the first bank to go bust borrowing short and lending long. It certainly won’t be the last. In fact, since SVB failed, Signature Bank has also failed. In addition, Credit Suisse is now getting a bailout from the Swiss National Bank. At this rate, any number of other banks could soon be toast.

Quite frankly, we don’t’ care what banks go bust. What we’re really interested in is what happens after these banks go bust. In the case of SVB, a bailout – above and beyond FDIC deposits – is in the works, through the creation of something called the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

What you need to know about BTFP is that it’s code for socializing losses. The regulators may say it isn’t a bailout. The taxpayer isn’t directly paying for it. Nonetheless, if you – the taxpayer – have a bank account, you will be picking up the tab via surcharges and fees your bank imposes to bailout SVB depositors. Is that fair?

Should you have to pick up the tab for California Governor Gavin Newsom’s wineries, billionaire businessman Mark Cuban’s drug company, or any of the other rich elites that failed to appropriately manage their risk?

On top of that, what will ultimately happen to the remains of SVB or other failed banks? Will the FDIC sell them off to one of the big banks like Washington Mutual (WaMu) was to JPMorgan Chase in 2008?

Government bailouts and the consolidation of the banking business does not make banking safer. Rather it spreads the risk across the whole landscape like mustard seeds on a hillside. This, in effect, propagates a much larger banking crisis sometime in the future.

It also propagates civil disorder and social discontent. And for what?

When banks merge and consolidate over and over again the implications can be heinous. To this point, for fun and for free, we’ll take a look back at the quintessential bank failure of the 20th century.

Where to begin…

Epic Bank Failure

In 1820, Salomon Mayer von Rothschild (1774-1855) established his business, S M von Rothschild, Vienna. Vienna was the capital of the Austrian Empire at the time.

When S M von Rothschild died in 1855, his son Anselm von Rothchild (1803-1874) founded Credit-Anstalt as K. k. priv. Österreichische Credit-Anstalt für Handel und Gewerbe. This Rothchild bank became the largest bank in Eastern Europe before World War II.

Credit-Anstalt held assets and took deposits from all over Europe. Then, in 1931, it failed at the worst possible time.

The bank’s failure was a direct result of the United States’ Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods. The act crippled Europe’s economy and led investors to redeem all the capital they’d lent to the bank.

The failure of Credit-Anstalt caused Austria to abandon the gold standard, which set off a series of economic dominoes. Germany left gold. Then Great Britain. And finally, in 1933, so did America.

The failure of Credit-Anstalt is what really kicked off the Great Depression. The real story, of course, is not Credit-Anstalt’s collapse. It’s what let up to its collapse.

Today, with the Federal Reserve having first compelled banks to stretch for yield in long dated maturities, before then hiking short-term interest rates, banks are being put to an extraordinary test. Without question, there will be more SVBs in the coming weeks.

What’s more, a series of bank bailouts and consolidations could be the perfect setup for a very destructive Credit-Anstalt situation. The BTFP bailout of SVB – and Gavin Newsom – offers a pathway to a mega crisis.

Here’s why…

Forced Mergers

When the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed at the end of World War I, Credit-Anstalt continued to offer commercial, investment and savings to customers in both the former empire states as well as Amsterdam, Berlin, Bucharest, Paris, and Sofia. Its shares were traded on eleven exchanges, including New York.

Credit-Anstalt became the largest bank in Austria through a series of forced mergers to bailout other Austrian banks that had failed. These forced mergers may have been expedient. But they were not intelligent. That is, they did not always pencil out.

Moreover, it resulted in the creation of a bank that was larger than the rest of Austria’s banks put together. It also concentrated the accumulated losses of Austrian industry in a single super bank.

Over time, Credit-Anstalt’s balance sheet eclipsed the size of the government’s expenditures. Approximately, 70 percent of Austria’s corporations did business with it.

In 1925, Credit-Anstalt’s equity was only 15 percent of what it had been in 1914 (at the onset of WWI) and its debt-to-equity ratio rose from 3.64 in 1913 to 5.68 at the end of 1924. By the end of 1930 it had ballooned to 9.44.

Part of the increase in the size of the bank came from loans which Credit-Anstalt made to businesses of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. To make these loans, Credit-Anstalt borrowed money, primarily from Great Britain and the United States.

However, the loans from Great Britain and the United States were only on a short-term basis. Any failure to renew these loans would lead to the demise of the bank. The effect of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act essentially toppled the credit pyramid.

On May 11, 1931, the bank announced that it had lost more than half of its capital. This was a criterion under Austrian law by which a bank was declared failed. The announcement of losses led to a panic and bank runs on Austrian banks.

Occupy Wall Street Redux

The crisis that started in Austria and extended to the European continent, continued to Great Britain. The island nation went off the Gold Standard on September 21, 1931, after its gold reserves shrank from £200 million to £5 million.

Twenty-five countries soon followed in Britain’s footsteps, depreciating their currency against the U.S. dollar or leaving the gold standard. By the end of 1931, the Depression (with a capital D) was global.

FDR took the U.S. off the Gold Standard in April 1933, confiscated the gold of U.S. citizens, and devalued the dollar. By this, workers, savers, and taxpayers got a raw deal. They always do.

For example, during the 2008-09 great financial crisis and bank bailouts, workers, savers, and taxpayers also got a raw deal. They lost their jobs. They lost their houses. They lost their life savings. Yet the big bankers still got their big bonuses.

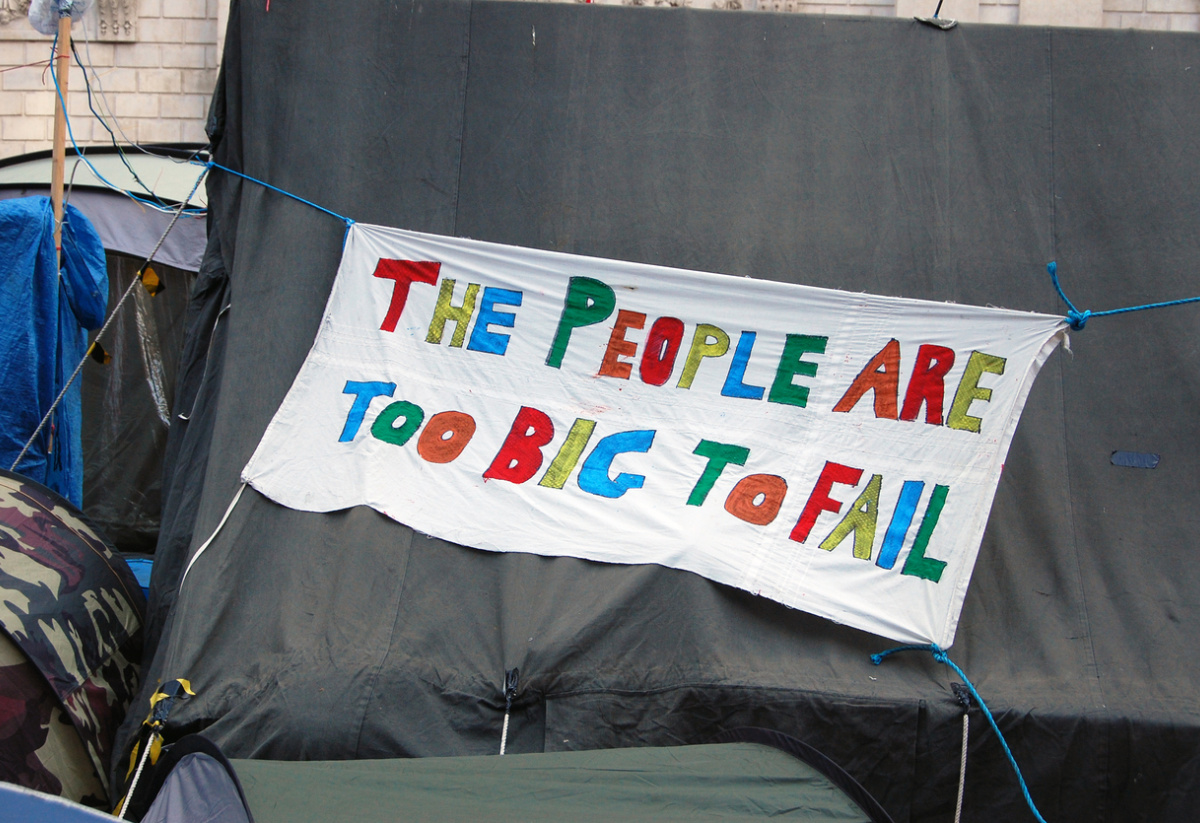

If you recall, these bailouts triggered major social discord where the 99 percent took to the streets to Occupy Wall Street. The current bailout of SVB depositors – above and beyond FDIC limits – is resurfacing these same strifes.

California Governor Gavin Newsom’s wineries got a bailout. Billionaire businessman Mark Cuban’s drug company got a bailout. Many other Silicon Valley rich elites got a bailout.

Therefore, shouldn’t students get a bailout of their student loans? Shouldn’t mortgage and credit card debt be cancelled? Shouldn’t RIFed Googlers get a bailout so they can keep making big bucks sitting in padded hypnotic meditation chambers?

These questions are absurd. But so are the bailouts of SVB’s big depositors and the further consolidation of the banking industry. What if, like Credit-Anstalt, JPMorgan Chase or Bank of America were to fail?

These are the grim opportunities that bank bailouts and bank consolidations make available.

After decades of prolificacy, followed by decades of ambivalence and apathy, America’s headed for complete financial, economic, and societal catastrophe. You can see it. You can hear it. You can feel it. You can taste it. You can smell it.

First stop: Occupy Wall Street Redux.

In closing, owning physical gold and silver has never been more critical.