Opinion

Why Totalitarianism Can Never Be Total

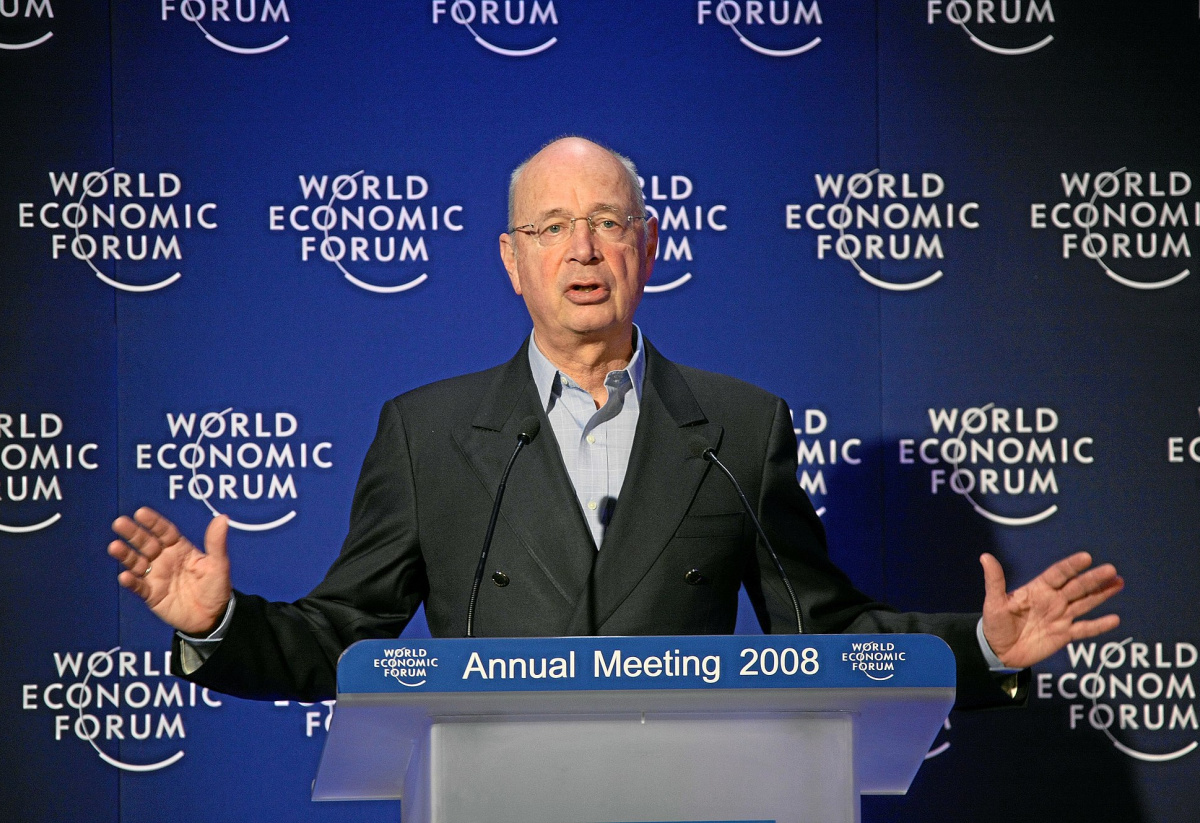

When reading a dissertation-chapter by one of my PhD-students, Marc Smit, recently, I was reminded of the relevance of philosopher Hannah Arendt’s work for the present Götterdämmerung we are living through. For make no mistake – it may be possible to resist Klaus Schwab’s vaunted “Great Reset,” but the world as we knew it before the advent of the Covid-19 ‘pandemic’ cannot be resurrected.

Nor should we regret this; taking into consideration everything that has come to light since the beginning of 2020, and which is still emerging, we should not want to go back to that world – we need a better world; we should want a better world than one so steeped in deception at multiple levels that it has given rise to the present crisis.

In Mr Smit’s dissertation he draws on Arendt to be able to reach clarification regarding, among other things, the question of the relation between tertiary education and ‘action’ in the Arendtian sense; to wit, the highest level of what she called the vita activa (the active, as opposed to the contemplative life), the other two levels being ‘labour’ and ‘work.’ While this is an important theme to pursue, what interests me here is rather the question of the desired action in the face of the continuing attempt to install a technocratic totalitarian regime in the world.

Totalitarianism is most readily associated with Hannah Arendt’s work, of course, and it is here that one encounters disconcerting similarities with what one might call the ‘totalitarian nihilism’ pervading the world today, keeping in mind that nihilism amounts to the denial of any intrinsic value: nothing has value – which is precisely what the perpetrators of the ongoing crime against humanity want to achieve, because when one values nothing, there is nothing to cherish, nothing to defend and fight for.

Consider the following passage from Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism – the part titled “Total Domination” (p. 119 of The Portable Hannah Arendt, Penguin Books, 2000) in the light of recent and current events globally:

The concentration and extermination camps of totalitarian regimes serve as the laboratories in which the fundamental belief of totalitarianism that everything is possible is being verified. Compared with this, all other experiments are secondary in importance—including those in the field of medicine whose horrors are recorded in detail in the trials against the physicians of the Third Reich—although it is characteristic that these laboratories were used for experiments of every kind.

Ignoring the question of concentration camps for the moment, recall that, for the globalist technocrats of today, as for the fascist ‘scientists’ of Nazi Germany, “everything is [indeed] possible,” particularly through advanced technology. Here is Yuval Noah Harari, supposedly Klaus Schwab’s chief adviser regarding the vaunted transhumanist (literally: surpassing humanity) agenda, expressing his beliefs regarding technology’s capacity to make humans into something ‘godlike,’ beyond humanity (Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, Signal, 2016, p. 50):

However, once technology enables us to re-engineer human minds, Homo sapiens will disappear, human history will come to an end and a completely new kind of process will begin, which people like you and me cannot comprehend. Many scholars try to predict how the world will look in the year 2100 or 2200. This is a waste of time. Any worthwhile prediction must take into account the ability to re-engineer human minds, and this is impossible. There are many wise answers to the question, ‘What would people with minds like ours do with biotechnology?’ Yet there are no good answers to the question, ‘What would beings with a different kind of mind do with biotechnology?’ All we can say is that people similar to us are likely to use biotechnology to reengineer their own minds, and our present-day minds cannot grasp what might happen next.

The statement, that one could provide ‘wise answers’ to the question, what people endowed with human minds would do (and are doing) with biotechnology, is an oversimplification, of course. Its formulation betrays the assumption that it is only a matter of mental capacity which determines the ensuing actions. But what about constraining factors, such as moral ones? Is it a matter of doing following automatically from capacity? Is everything that is technically possible, ipso facto imperative to be done?

Recall Arendt, above, writing that totalitarianism is predicated on the belief that everything is possible. I would argue that it is no different for Harari, or Schwab, or Bill Gates. In widely circulated video-interviews more recently, Harari has confidently proclaimed that “humans are hackable animals,” which has the sinister implication that he – and no doubt Schwab and Gates as well – regards humans as the equivalent of computers and/or software programmes, which can be ‘hacked’ to gain entrance to them, usually with the intention of modifying or appropriating some desired ‘content.’ More importantly, there is nothing to suggest that ethical considerations stand in their way, as was also the case in the Nazi laboratories Arendt alludes to.

That the road to the actualisation of this totalitarian scenario has been prepared for some time is apparent from the work of Shoshana Zuboff. In her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism – The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (Public Affairs, Hachette, 2019) she alerts readers to what seems to be a novel, almost invisible, incipient totalitarianism, of which the vast majority of people are unaware as such.

Moreover, they voluntarily embrace the way that the powerful agencies behind this pervasive surveillance rule their lives in a virtually ‘total’ manner. Right at the beginning of her book Zuboff offers a revealing characterisation of this phenomenon (“The Definition”):

Sur-veil-lance Cap-i-tal-ism, n.

1. A new economic order that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales;

2. A parasitic economic logic in which the production of goods and services is subordinated to a new global architecture of behavioral modification;

3. A rogue mutation of capitalism marked by concentrations of wealth, knowledge, and power unprecedented in human history;

4. The foundational framework of a surveillance economy;

5. As significant a threat to human nature in the twenty-first century as industrial capitalism was to the natural world in the nineteenth and twentieth;

6. The origin of a new instrumentarian power that asserts dominance over society and presents startling challenges to market democracy;

7. A movement that aims to impose a new collective order based on total certainty;

8. An expropriation of critical human rights that is best understood as a coup from above: an overthrow of the people’s sovereignty.

Needless to emphasise, in retrospect Zuboff’s perspicacious ‘definition’ is easily recognisable – almost item for item – as something almost prophetic concerning the events of the last three years as well as those still in the offing, although she was ‘only’ referring to the agencies that fundamentally influence most people’s lives today, such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat.

For one thing, Harari’s observations on the ‘engineering’ of human minds resonate chillingly with her warning about a “threat to human nature.” For another, the disconcerting ability of these ‘surveillance’ companies to censor the truth about the sustained attempt to rob people of their humanity is clearly connected to their ‘instrumentarian’ capacity of enforcing a ‘new collective order’ rooted in ‘certainty,’ and (more startling still) of ‘expropriating’ the human rights that have been taken for granted for decades.

Against this backdrop, any person who has not been living under a proverbial rock would know that, if we cherish our freedom, resistance is our only option. In this regard Jacques Lacan famously compared the ‘mugger’s choice’ with that of the ‘revolutionary.’ The former amounts to this; ‘Your money or your life,’ and represents a lose/lose situation; either way, you would lose something.

The revolutionary’s choice, however, is a win/win situation – although this may appear counter-intuitive: ‘Freedom or death.’ Whatever you choose here, you win, because in both instances one would be free – either free from oppression, having vanquished the tyrant, and hence free to live in liberty; or free from oppression in death, having fought against the oppressor and lost one’s life as a free person.

Today there are millions of people across the globe (some of them comprising the ranks of those associated with Brownstone Institute) who have chosen to do battle against the technocrats who believe that they are invincible. The latter have miscalculated their anticipated triumph in an irreparable manner, however.

Not only is it impossible to colonise the human spirit irresistibly; putting it in Arendt’s words, human beings are constituted, among others, by two inalienable existential conditions: natality and plurality. As the word suggests, ‘natality’ – the givenness of having been born into the world – marks a novel addition to the human race, comprising a new beginning, as it were. ‘Plurality,’ in turn, indexes the irreversible fact that no two humans in the entire history of the species have ever, nor could ever be, exactly the same – not even so-called (genetically) ‘identical’ twins, who often display markedly different interests and ambitions. Paradoxically, each one of us is unique, singular, and therefore we are irrevocably plural, irreducibly different. Arendt elaborates on these two qualities as follows in The Vita Activa (The Portable Kristeva, p. 294):

Unpredictability is not lack of foresight, and no engineering management of human affairs will ever be able to eliminate it, just as no training in prudence can ever lead to the wisdom of knowing what one does. Only total conditioning, that is, the total abolition of action, can ever hope to cope with unpredictability. And even the predictability of human behavior which political terror can enforce for relatively long periods of time is hardly able to change the very essence of human affairs once and for all; it can never be sure of its own future. Human action, like all strictly political phenomena, is bound up with human plurality, which is one of the fundamental conditions of human life insofar as it rests on the fact of natality, through which the human world is constantly invaded by strangers, newcomers whose actions and reactions cannot be foreseen by those who are already there and are going to leave in a short while.

In a nutshell: through natality new beginnings come into the world, and through plurality these actions are different from one person to the next. As Arendt suggests here, ‘political terror’ can enforce uniformity of behaviour for comparatively long periods of time, but not forever, for the simple reason that natality and plurality cannot be erased from humans, even if it might be possible to eradicate them from a technically engineered creature that would no longer answer to the name ‘human.’

We are able to resist these would-be dictators in so far as, through our actions, we instantiate new, unpredictable beginnings, sometimes by rupturing fascist, totalitarian practices. Whether it is resisting their attempt to enslave us through the introduction of so-called Central Bank Digital Currencies – ‘programmed’ pseudo-money which would limit what one can do with it – or through the impending ‘climate lockdowns’ that aim at restricting freedom of movement, being persons endowed with natality and plurality means that we will not be a pushover.

This article originally appeared in the Brownstone Institute.